An image of Our Lady of Czestochowa adorns St. Stanislaus Church in Omaha. SUSAN SZALEWSKI/STAFF

News

Praying through the eyes: visio divina

April 22, 2022

Through his eyes, Benedictine Father Pachomius Meade encounters God – in the rolling hills surrounding his home at Conception Abbey in Conception, Missouri; in the religious imagery at the abbey and its Basilica of the Immaculate Conception; in the beauty of secular art.

He helps others encounter the Lord through the icons and artwork he creates at Conception, including the seminarians from the Archdiocese of Omaha who study at Conception Seminary. There Father Pachomius is dean of students, as well as an iconographer, artist and art historian.

Benedictine Father Pachomius Meade teaches an iconography course last fall to students at Conception Seminary in Conception, Missouri. COURTESY PHOTO

Praying and meditating on what one sees – in icons, art and nature – is an ancient form of prayer. Some use the term visio divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” to describe this form of prayer. It crosses the lines of religious denominations and is part of the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, and extends to many Protestant denominations.

Father Peter Pappas, a Greek Orthodox priest, says heaven opens up every time he gazes at one of the many icons that surround him at St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church in Omaha, where he is pastor. With every gaze, a new level of meaning and understanding can be found as God speaks, he says.

Jane Tancredi, of All Saints Episcopal Church in Omaha, has helped people encounter God through icons she’s prayerfully created for Lutheran and Presbyterian churches, for individual homes and more.

Tancredi and students from a variety of faiths in her iconography classes – including some classes at the St. Benedict Center in Schuyler – continue an ancient Christian tradition by leading people to God through their icons.

With icons – as well as with art and nature – people open their eyes to meet the Lord in a prayerful exchange.

MEDITATING THROUGH ICONS

Visio divina is similar to another ancient form of prayer, lectio divina, Latin for “divine reading” of Scripture or other holy writings. Both visio divina and lectio divina lead people to pray and ponder through what they either see or read.

Understanding lectio divina might help a person understand visio divina, Father Pachomius said. People who’ve tried lectio divina should be able to transition from meditating on words into meditating with icons, which are not just art but sacramentals, he said.

“Sacramentals … prepare us to receive grace and dispose us to cooperate with it,” according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

“I really like a lot of Western art, religious art, so I don’t want to discount it,” Father Pachomius said. “But the one thing about iconography is that it’s not just a painting. It’s a sacramental, like a rosary or holy water. … It’s really meant to be a window into heaven.”

The subjects of an icon are made “present from heaven to you right there,” he said. “That intermediate thing of wood and gold leaf and paint gives you a contact point with the divine. So not only are you contemplating this image, but in the theology of it, the person depicted, who is really in heaven … is kind of made present there and contemplates you.”

Creating icons based on Scripture is what Tancredi calls making the Word visible. She prays with and studies the Scripture passages that she helps bring to life. Prayer is infused into the entire creative process, she said.

“You’re writing this prayer,” she said.

She uses the words “writing” and “reading” because icons are the written word of Scripture made visible through iconography.

Jane Tancredi, of All Saints Episcopal Church in Omaha, applies gold leaf to an icon at her studio in Omaha. SUSAN SZALEWSKI/STAFF

“Icons are a great focus for prayer,” Tancredi said. They’re meant to help people become silent and prayerful as they listen, see and read the icon.

Both she and Father Pachomius were trained by master teachers in iconography.

Tancredi, who said she always loved art, was a nurse for 32 years before retiring. She considers nursing and iconography her two ministries. Her husband, the Rev. Michael Tancredi, is a retired Episcopal priest who served at All Saints.

Father Pachomius has master’s and doctorate degrees in art history from the University of Missouri. “He enjoys making present the heavenly realm with sacred images,” according to his biography on the abbey’s website.

EYES OPEN

People praying with icons shouldn’t close their eyes as they pray, Father Pachomius said. Because, as he emphasizes, “With an icon, you’re looking into heaven.”

“You would pray through these icons – as opposed to looking at them, closing your eyes, imagining something happening, looking at it again and doing the same thing over again. You never stop looking at an icon as you pray. Even in the Western Church, that’s the way to approach these.”

Icons are part of an ancient tradition of prayer, begun in the early Church and passed on in particular in the monastic tradition in the Roman Catholic faith.

Icons have an especially important role in the worship of the Eastern Church, which was separated from the Roman Catholic Church in 1054.

Father Pappas points to icon details at St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church. Greek lettering reveals Jesus as the Christ, as the Beginning and the End, and as the great I AM revealed to Moses.

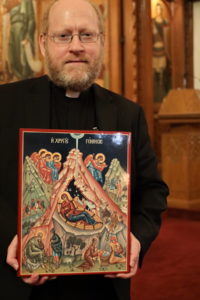

Father Peter Pappas, pastor of St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church in Omaha, displays a Nativity icon. SUSAN SZALEWSKI/STAFF

An image of the Nativity portrays several events at one time: Jesus in a cave that served as a stable, wrapped in swaddling clothes that prefigure how he’ll be wrapped for burial; Magi making their way to Jesus, guided by a star; angels announcing the birth to the shepherds; a devil talking to St. Joseph, trying to put doubts in his mind about all the things that are happening.

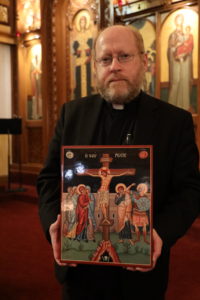

In an icon of the crucifixion, the sun and moon represent creation in the context of the cross, Father Pappas said. A sign on the cross identifies Jesus not as the king of the Jews, as described in the Gospels, but as the king of glory.

“You’ll notice it’s not attempting to depict the horror of the suffering on the cross, but the victory of suffering love. So we see Christ as the crucified one, but as the victor as well.”

“We’re seeing that through his sacrifice he is establishing his kingdom,” Father Pappas said. “We see down here the skull and bones,” he said, pointing to the icon, “which represent the bones of Adam and Eve. What this is showing is that Christ gives his life. His blood flows down to cleanse all that came before, all the way to the very beginning, to Adam and Eve.

Father Pappas shows an icon of the Crucifixion. SUSAN SZALEWSKI/STAFF

“Then we see the figures who are at the crucifixion: the centurion, John the apostle and the Mother of God. The Theotokos (Greek for Mother of God or God-bearer) is there, together with the other women.”

The centurion has a halo in the icon.

“We know from the Gospel that he confessed ‘Truly this was the Son of God,’” Father Pappas said. “So that’s viewed as his conversion and his witness.”

Sometimes in icons of the crucifixion, the horizontal bar of the cross is shown as tipping up, toward the good thief who repented, and down toward the unrepentant criminal on the other side of Jesus.

“A number of levels of meaning in the singular image,” Father Pappas said.

NATURE, RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR ART

“If God created nature, it should be good enough for us” for meditation, Father Pachomius said.

“But there’s a danger with that, that it becomes whatever you want it to become,” he said. “Someone who is a mature Christian can look at creation and say ‘Oh, wow! I can think about how all this comes from God the Creator, and how he’s planned everything. But it could also turn into ‘I’m going to go pantheistic and worship this tree.’ And we don’t want to do that.”

God can be found in secular art, too.

“Be open-minded about different forms of art,” Father Pachomius said, “even if it’s not what immediately speaks to us.”

Religious art is helpful because it intentionally guides viewers to the divine.

“The helpful thing about religious art and representational art is that it does focus me a little bit,” Father Pachomius said. “It gives me limitations, it gives me corners, so that I’m not led in whichever way.”

In visio divina and all prayer, people need to discern whether they are hearing or seeing God.

“Base it off of what we know in tradition and the teaching of the Church and with people who are wise in discerning spirits, someone who is experienced, like a spiritual director or priest,” Father Pachomius suggested.

Some knowledge of the art helps, too.

“If you just explain a little bit, that goes a long way with people’s appreciation of it,” he said. “When I was a pastor, we had these stained glass windows that were beautiful, but they didn’t have names of who the saints were.

“Part of the anxiety people had was they just didn’t know who they were. So once you identify the symbols – the attributes they have, why they’re doing what they’re doing – people really wanted to know more, and I think they wanted to pray more with them. A little bit of knowledge goes a long way.”

“Having some understanding of what it’s representing is usually a good thing,” he said. “But again, I don’t want to discount an intuitive level.”

“We talk about the three transcendentals that are sourced in God: goodness, truth and beauty. So an appreciation of beauty is a way to be attracted to the divine.”

A LIFESTYLE OF VISIO DIVINA

People tend to think in images rather than words, Father Pachomius said.

“If I say cabbage to you, you don’t think of a word in your mind. You think of a picture of a cabbage. That’s how we tend to organize information in our heads.”

With images reflected upon in prayer, “you could think back on those throughout your day, and the different things that you would see that might be included in those pictures would be a little bit of a hook to draw you back into prayer,” he said. “So as you went about your day, you’d have something to think about, to pray about, throughout your whole day.

“That’s the point of pictures. They become mental images for you. In fact, that’s what some of the reformers disliked most about images, not just that they were (considered) idols.”

When entering an Eastern Catholic or Orthodox church, the aim is to enter heaven, Father Pachomius said.

“For the East, it’s like going to heaven, like you leave earth and are surrounded by the saints and angels and Christ and the Blessed Virgin. They’re all right there. You are sucked up into heaven, right then and there.”

Benedictines tend to “have a lot of art everywhere,” Father Pachomius said. “We do tend to surround ourselves with art. Our life is about stability, about living in a place and learning to find it beautiful.”

“In the culmination of your life, you see these little things, and they add up over time.”

‘LET IT PENETRATE YOUR HEART’

“For anyone to really have fruitful prayer, you have to sit with something,” Father Pachomius said. “There’s a contemplative quality to looking at art properly, in the same way that there is to coming to Scripture.”

A person has to take the time to “let it penetrate your heart enough,” he said. “There’s a slowness that all these things take, and all of us are used to social media, a smartphone and streaming video. We always have to detox from it in order to really appreciate it. It’s harder and harder to do. Everybody’s capable of doing it, I think, but you have to be deliberate about it.”

At the monastery, “that’s something that we’re formed in here to do, and we take time out of our day to go and do it.”

There are methods for visio divina, steps for beginners to try out, including some on Catholic websites.

But Father Pachomius invites people to simply take time and sit with an image, whether it’s an icon, religious art, secular art or nature.

“People have been conditioned to say ‘What does this thing mean? Give me a bullet point. And that’s the wrong way to approach churches, art and prayer. If you expect to only get one thing out of prayer, one time on the first go, then you’re never developing a relationship with Christ.”

That would be like going to an ATM, Father Pachomius said. “And that’s what we do. Give us this day our daily bread.”

“I’m called to be a child of God, one who has a loving relationship with my Father. So I think there’s much to be reclaimed in touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing that … we’ve been kind of deconditioned to appreciate. That’s a societal thing, but our people haven’t really been conditioned to do that.”

Catholics have become “very cerebral in our worship and prayer,” not fully using their senses to take in “the smells and bells” of worship, he said.

“I think we have to reclaim in a certain way that prayer is not just about talking, or even only about listening in a verbal way, but also being touched by something really beautiful and not having the words to describe it and being very moved or grateful to God and feeling very close to God,” the priest said.

“Like when we talk about an experience of something that’s awesome, when you climb a mountain and you look out, and you’re both terrified and just thrilled. That’s part of what prayer should be.

“I think it’s not just something that I can describe in words, but something that touches me on a deeper level,” he said. “Contemplation is something that transcends simple understanding. I don’t get it all at once.”

“Paintings, statues, stained glass windows, icons – they don’t say just one thing,” Father Pachomius said. “They say many things, and they add up over time. So you can’t really get it all at once.”