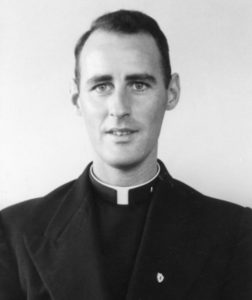

Refusing to abandon his flock, the late Father Thomas Cusack (INSET PHOTO COURTESY OF THE COLUMBAN FATHERS) was killed during the Korean War with other Columban Fathers missionaries. PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY JIMMY CARRROLL/STAFF

News

Two missionaries, one a martyr who refused to leave his flock, are connected by name, vocation and family

November 11, 2022

“I am the good shepherd. A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.” – John 10:11

Columban Father Thomas Cusack was an Irish missionary priest who wouldn’t abandon his flock in South Korea when enemy forces closed in during the Korean War.

Within weeks, in 1950, he was killed because of that decision.

To his parishioners, Father Cusack was their beloved “Iron Man” because of his taxing workload and the ultimate sacrifice he made.

For a wounded U.S. infantryman and fellow prisoner of war – the late Capt. Alexander Makarounis – Father Cusack and two other Columban Fathers were a source of hope, comfort and prayer.

For Archbishop Hyginus Hee-joong Kim of Gwangju, South Korea, Father Cusack remains a source of inspiration, though the archbishop likely would have no direct memories of the priest who baptized him as an infant. Yet, as Archbishop Kim wrote, he must follow Father Cusack’s “precious pastoral spirit as he has offered his life for his flock.”

Meanwhile, more than 6,000 miles away, in the Archdiocese of Omaha, Father Cusack and his martyred missionary companions are remembered at the regional headquarters of the Missionary Society of St. Columban in Bellevue.

For one of the Bellevue priests in particular, who’s also named Father Thomas Cusack, there’s a deeper connection. The late Father Cusack was his first cousin, who shared not only his name but also a vocation as a Columban Fathers missionary.

Columban Father Thomas P. Cusack, part of the Missionary Society of St. Columban in Bellevue, is pictured earlier in his priesthood. Now 89, he lives in Bellevue at the Columban Fathers’ headquarters. He is the cousin of another Columban Father missionary who is believed to be a martyr for the faith. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE COLUMBAN FATHERS

Father Thomas P. Cusack, now 89, never served in Korea like his cousin, but served instead in the Philippines and the United States.

He was a teenager in Ireland when his cousin was killed. For him and other family members, the loss of life was deeply personal.

When they learned of their loved one’s death, “We were heartbroken,” Father Cusack recalled in a recent interview. “But very soon our sorrow was turned into joy because what we came to realize was that we now had a martyr in the family.”

Family members “were very, very proud of him and the way that he stayed with” his South Korean flock, Father Cusack said.

HARDSHIPS

An age gap of about 30 years separated the cousins. The elder Father Cusack was ordained in 1934, a year after his younger cousin was born. Their fathers were the oldest and youngest of the Cusack siblings in Ireland.

The newly ordained priest was sent to Korea, and his hardships began, including being imprisoned by the Japanese for 3½ years during World War II.

Korea was a tough place to live and have basic necessities, Father Thomas P. Cusack said.

“He did the best that he could. He had very good health. He was excellent at the language, and he was a hard worker. He loved the Korean people, and he had a great depth of faith and commitment to the priesthood, to the Church.”

The life of a missionary is often difficult and dangerous. A Martyrs Memorial Garden on the Columban grounds in Bellevue attests to that.

The garden honors more than 20 Columban Fathers from the past 100 years who have been martyred, including Father Cusack, who is believed to have been martyred with his two Columban priest companions in a massacre of prisoners in Taejon, South Korea, on Sept. 24, 1950.

A total of seven Columban Fathers were martyred in Korea during the Korean War.

Father Cusack’s young cousin was able to spend precious time with him while on a yearlong break at home in Ireland after World War II. It was an overdue reunion with family because Father Cusack had been in Korea for 13 years without a break. During his year at home in Ireland, the missionary spent a month at the home of his cousin’s family.

“So I got to know him at that level of having a priest live with us,” Father Thomas P. Cusack said. “Up to that time, our only experience of priests was just meeting them and having kind of a formal relationship with them.

“He told us great stories about Korea, about the Korean people and about his time in jail.

“He used to go off to various functions, and he would come back with rosary beads and little statues and things like that. I can remember going into his room one night, and there he was on the floor. He had about 20 little bundles of rosary beads and little statues and prayer cards. They were for all the different people in his parish.

“He brought his people with him wherever he went,” the younger cousin said.

‘I’LL STAY’

Then it was time for Father Cusack to return.

“He went back to Korea at the end of the year and in 1950 became the parish priest in Mokpo … in the southern part of South Korea,” his cousin said.

“While he was there, the communists came across the 30th parallel from North Korea into South Korea. Of course the United Nations sent in forces, but they hadn’t established themselves.”

“There was a beautiful account written by an American officer,” Father Thomas P. Cusack said. “He went to Father Tom, and he said to Father: ‘The communists are going to be here in a very, very short length of time. We can evacuate you now. But if you don’t come now, you are on your own.’

“He said that Father Tom just thought for a minute and said: ‘You know, there isn’t enough that I can do by staying with the people, but the good shepherd doesn’t leave his sheep untended. So I’ll stay with them.’

“And he stayed with them. He was captured by the communists and put on a death march up to North Korea. There were a lot of people who were very weak and weren’t able to travel and were going to slow down the others, and the United Nations were closing in on them. … One night they put them into an old barn, and they burned them all to death. Then they threw their bones down a deep well. Of course, when those bones were recovered, there was no DNA or anything like that.

“So all we know is that his remains were in there. When we heard of it in Ireland, we were devastated because we had come to know somebody and to love that person and have a relationship with him.”

During imprisonment, Father Cusack and the other Columban Fathers – Msgr. Patrick Brennan of Chicago and Father John O’Brien, also from Ireland – refused to provide the names of the Catholics who’d been under their care.

When they were initially taken into custody, the priests were separated for a while, questioned individually and accused of being spies, according to Capt. Makarounis’ recollections.

Meals were meager, he said. When he met the three Columban Fathers, five weeks after the priests were taken into custody, they all had lost considerable weight, he said.

Yet they cared and comforted those imprisoned with them.

“I will never forget these three Columban missionaries,” Makarounis said in his testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee on Korean War atrocities, “for we were put in the cell with them in the early morning hours. The first morning that I awoke and turned over, opening my eyes, they were looking at me, kind of smiling.”

There weren’t enough blankets for the new prisoners, but the priests had offered theirs, Makarounis wrote in a different account about the Columban Fathers, called “I Met Them in Jail.”

“It was the first of many acts of kindness and consideration the priests were to show us during the dreadful days we were to go through,” Makarounis wrote.

SINGING, DANCING, PRAYING

The priests were arrested about a week after the war started and had expected to be killed immediately, he had learned.

“They, all three, expected to be shot, but it didn’t seem to bother them,” the soldier said in his Senate testimony. “If it did, they didn’t let on.”

Instead, they sang, danced jigs and prayed.

“It would be hard to tell you just what these men did for our morale – they boosted it by at least 500 per cent!” Makarounis wrote.

The priests would pray when friendly forces flew overhead, strafing and bombing the city of Kwangju, where they were jailed.

“At the times of those raids, I could see the lips of the missionaries moving in prayer,” Makarounis said in his Senate testimony, “and, although we could hear the crashing of bombs all around, we came through without a scratch.”

“I shall always remember them for the comfort, cheerfulness, kindness and courage they somehow communicated to us when they were no better off themselves,” he said.

In 2003 Father Thomas P. Cusack went to South Korea “to walk in Father Tom’s footsteps” and meet some of his former parishioners.

He has corresponded with one of them – Archbishop Kim.

‘PRIVILEGED’

In one of the letters Father Cusack wrote:

“We are very proud, in the good sense of the word, to have a martyr for our Catholic faith in the family.”

The archbishop replied:

“As you wrote me that you were blessed and privileged to have a martyr for the Catholic Faith in your family. Also I am blessed and privileged to have had a martyr baptize me.

“I think I have to follow his precious pastoral spirit as he has offered his life for his flock. The martyr, Father Tom Cusack, sowed his evangelical spirit through his martyrdom, and I think that his spirit must be alive through my faithful pastoral life.”

Father Cusack’s name was included in an official book of martyrs for the faith who died during the 20th century. The book was presented to Pope St. John Paul II in the Coliseum in Rome on June 29, 2000.

Father Cusack could eventually be canonized. The Church in Korea has taken up his cause for beatification, though the process is still in its early stages. “These things take a long time,” Father Cusack said.

But for his family, “whether or not he’s formally proclaimed a martyr by the Church, it’s not that important,” he said. “Because we know that he is.”